|

DAVID J. WAGNER, L.L.C.AMERICAN WILDLIFE ARTProduced by David J. Wagner, L.L.C.

ALLENTOWN ART MUSEUM "David Wagner is a distinguished

curator and art historian whose scholarly and informed contributions to

the field of art, particularly wildlife art, have set standards for

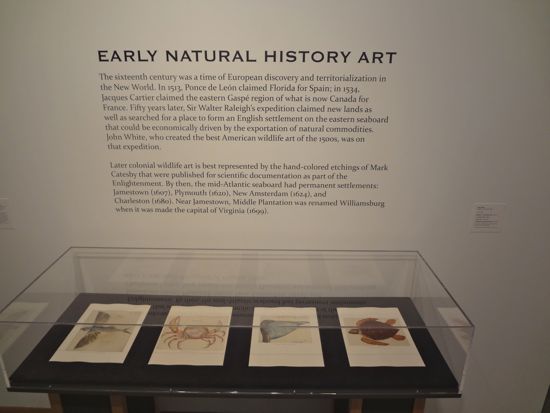

excellence, innovation, and thoroughness." ARTISTS EXHIBITION SYNOPSIS The book, American Wildlife Art, traces the history of a genre shaped by four centuries of aesthetic and ideological appropriation, from its beginnings in colonial times to works by influential artists of the present day, and explains how aesthetic idioms and imagery have evolved, how its ecological ideologies have changed with changing circumstances and ideas about animals and their habitats, and how artists and entrepreneurs developed and influenced the market for wildlife art. The book serves as a foil for the exhibition. The exhibition begins with the works of John White and Mark Catesby, artists who documented the flora and fauna of the New World and presented Europeans with a view of both the economic potential and the natural wonders of the then sparsely settled continent. After the American Revolution, as the new nation grew, artists such as Alexander Wilson and especially John James Audubon caused the course of American wildlife art history to turn and advance again. They set the stage for Arthur Tait and his collaboration with Currier & Ives, which brought wildlife art to the masses and re-focused the genre on sport. Edward Kemeys’ seminal sculptures captured the essence of disappearing wildlife like the American bison at the same time that prominent Americans like George B. Grinnell, William Hornaday, and Theodore Roosevelt were promoting wilderness preservation and the ethics of sportsmanship. Works by the second generation of sculptors who followed are also featured in this exhibition. Contemporaries Louis Agassiz Fuertes and Carl Rungius, were extraordinary painters who professionalized the genre and brought it into the Twentieth Century. Rungius introduced an aesthetic of impressionism which was shaped by the introduction of modernism in America through the Armory Show of 1913, while Fuertes, whose mentors were painter Abbott Thayer (who pioneered art of camouflage) and ornithologist Elliott Coues, introduced a new penetrating kind of imagery that Roger Tory Peterson subsequently described as "wildlife art gestalt." The exhibition continues with federal duck stamps and duck stamp prints, decorative carvings by the Chesapeake Bay’s Ward Brothers and carvers who followed, diorama-like paintings of Francis Lee Jaques, plus contemporary artists including Stanley Meltzoff (progenitor of dive art), Robert Bateman and Kent Ullberg whose work at once departs from and embodies the legacies, traditions, and innovations that informed and preceded it. EARLY NATURAL HISTORY ART Really great, sixteenth-century American wildlife art is hard to find and rare. Of work that remains today, the subtle watercolor drawings of John White are the best. Symbolized by it’s famous and, sometimes, infamous explorers, the sixteenth century was a time of European discovery and territorialization in the New World. In 1513, Ponce de Leon landed in Florida and claimed it for Spain; in 1534, Jacques Cartier landed in the eastern Gaspe region of what is now Canada and claimed it for France. Fifty years later, in 1584, Sir Walter Raleigh outfitted a reconnaissance expedition that foreshadowed a new epoch in America’s history. The purpose of the expedition was not merely to discover and lay claim to new lands. Raleigh was searching for a location for an English settlement on North America’s eastern seaboard that could be economically driven by the exportation and consumption of abundant natural "commodities," as furs or salted fish, for example, were called then. John White was among the members of that expedition, and subsequent expeditions. Later colonial American wildlife art, produced during the Enlightenment when Williamsburg was the capital of The Virginia Colony, is represented at its best by the didactic, hand-colored etchings of Mark Catesby that were published for scientific documentation and study of natural history. By then, America’s mid-Atlantic seaboard had been populated with permanent settlements. The first of these was established in 1607 and named Jamestown. Founded further north in 1620, Plymouth became the first permanent settlement in New England. New Amsterdam, as New York was called, was established in 1624. In 1632, Middle Plantation was settled not far from Jamestown and renamed Williamsburg when it was made the capital of Virginia in 1699. Not long before that, in 1680, Charles Town, later Charleston, was founded as the capital of the new colony of Carolina, and John James Audubon would work there some 150 years later. EARLY COLONIAL AMERICAN WILDLIFE ART JOHN WHITE Early colonial American wildlife art is exemplified, at its best, by the subtly alive watercolor drawings of John White. Not much is known about White. Biographers have determined that he was born between 1540 and 1550 in London, and died in England around 1606. In addition to taking part in Raleigh’s 1584 reconnaissance expedition and the attempt to plant a colony there in 1585–86, White he set sail for a third time in 1587, this time not as an artist but, rather, as governor of what would become the fabled Lost Colony of Roanoke. To create his watercolor drawings, White drew outlines of his subjects on paper in black lead and filled in the resulting shapes by shading and stippling them with watercolors. As a draftsman, White was particularly adept at outlining the shapes of his subjects and rendering them in proper proportion. As a watercolorist, one of White’s special talents was using small brush strokes to capture the detail and texture of fur or fish scales or the markings of a given species. He was also able to evoke three-dimensional form by delicately modulating colors. White’s subtle and restrained use of watercolor created a sense of immediacy and freshness that made his remarkable early works come alive. LATER COLONIAL AMERICAN WILDLIFE ART MARK CATESBY Later colonial American wildlife art, produced during the Enlightenment, is represented at its best by Mark Catesby (1682/83-1749) and his hand-colored etchings. Catesby made New World wildlife and plants available for science in Natural History of Carolina, Florida, and the Bahama Islands, the first color-plate book on American natural history. Catesby can take credit for five notable accomplishments: he searched for and discovered numerous New World species previously unknown to science; he wrote the text for his book without the aid of formal training in science; he composed the imagery for his book without the aid of formal training in art; he learned the process of etching in order to bring his book to market; and, along the way, he became his own publisher. This kind of enterprise, in which a single mercantile entrepreneur carried out virtually every phase of production, would be increasingly replaced by commercial specialization in the nineteenth century. Mark Catesby is significant in the history of American wildlife art because he founded practices upon which others would establish themselves later on. THE NEW U.S. MILIEU AND THE RACE TO PUBLISH BIRDS The next episode in the story of American wildlife art did not begin until the first decade of the nineteenth century, more than fifty years after Mark Catesby completed his Natural History. This episode unfolded as a race of sorts to discover and portray birds. It resulted in the publication of two new works. The first, American Ornithology, contained 320 portraits of birds attributed to Alexander Wilson. The second, the incomparably more lavish publication Birds of America, contained 457 bird portraits attributed to John James Audubon. In reality, however, this episode was more complex than a simple race. It reflected the enormous changes that had occurred in America since Catesby published his work, notably, the American Revolution, which consumed the attention of people on both sides of the Atlantic, and coast-to-coast exploration and settlement. THE FATHER OF AMERICAN ORNITHOLOGY ALEXANDER WILSON American Ornithology, by Alexander Wilson (1766 –1813), was the first color-plate book of American wildlife art ever printed and published in the United States. By focusing the systematic scientific methods that grew out of the Enlightenment on American birds, Wilson earned the epitaph, “father of American ornithology.” Wilson studied and knew the existing literature on American birds and the art that it contained, and he observed, dissected, described, and interpreted birds with greater breadth, depth, and precision than anyone else had before him. Wilson drew and described 264 American bird species during his lifetime, and added 48 new species to those already known. By publishing bird species that had been discovered by Lewis and Clark, Wilson extended the territory documented by American wildlife art across the continent to the Pacific Ocean. He initiated printing and publishing of wildlife art on North American soil; established ornithology as one branch of the biological science of natural history in America; and was the first to do all of this in the new nation of the United States. He also precipitated, as a catalyst, the unsurpassed accomplishments of John James Audubon. THE EPISODE OF JOHN JAMES AUDUBON The accomplishments of John James Audubon (1785 – 1851) culminate the epoch of exploration and appropriation that began with John White and were extended by the art, science, and enterprise of Mark Catesby and Alexander Wilson. Audubon was blessed with exceptional talent, but without his strength of character and his flair for showmanship, he would not have achieved greatness. Audubon distinguished himself as a creative and prolific artist, an insightful and inquiring naturalist, an entrepreneurial publisher, and the tenacious force behind Birds of America. Considering that North America has some 654 species of indigenous birds and that Audubon never made it to the Rocky Mountains, the fact that Birds of America represents 457 bird species (not to mention that Audubon painted 1,069 separate images for his book), is remarkable. But that’s not all. Audubon prolifically documented his findings in writing, and published Viviparous Quadrupeds in collaboration with Reverend John Bachman of Charleston. As a publishing entrepreneur, Audubon transcended his times by developing and perfecting enterprising marketing and production methods, which gave rise to and, in fact, became hallmarks of publishing during the Industrial Revolution. A self-reliant woodsman who drew on his wit and experience rather than on fashionable ideologies like Manifest Destiny, Audubon was a visionary who observed and expressed concern that wildlife depletion went hand-in-hand with national expansion. Above all else, however, Audubon was the gifted artist and inquiring naturalist who was the force behind Birds of America, the greatest wildlife art publication in history. MID TO LATE NINETEENTH CENTURY: DEMOCRATIZATION AND RE-APPROPRIATION Between 1850 and 1852, several events took place that profoundly affected American wildlife art. These events occurred as New York was emerging as the center of art for the nation, as outdoor recreation, particularly hunting and fishing, and much of that in The Adirondacks, was emerging as a leisure pursuit among masses of increasingly affluent Americans, and as an affordable print culture emerged out of the technology of lithography. In 1851, a thirty-nine-year-old publisher who had a knack for being in the right place at the right time noticed a painting by Arthur Tait. The publisher’s name was Nathaniel Currier. Five years later, he would partner with his bookkeeper, James Ives to form a company that they advertised with slogans such as “Print-Makers to the American People.” From 1852 to 1864, their chief supplier of wildlife imagery was Arthur Tait. As a consequence, expensive natural history folios such as those produced by John James Audubon would be eclipsed in the marketplace by cheap and affordable prints that portrayed wildlife not for the sake of science but as game for sport. Underlying this context and the democratization of American wildlife art was the Industrial Revolution. THE DEMOCRATIZATION OF AMERICAN WILDLIFE ART ARTHUR F. TAIT On September 3, 1850, a struggling artist named Arthur F. Tait (1819–1905) disembarked a ship from Liverpool and set foot in New York. Enjoying the twilight of his life at the rural northern tip was John James Audubon. He was sixty-six years old. Tait was thirty-three. Although Tait was adept at painting and printing bucolic landscapes and images of domestic animals and hunting parties, he came to American because he had no hope of breaking into a marked dominated by the likes of Edwin Landseer, a favorite of the British public and Queen Victoria. Arthur Tait played a central role in the democratization of American wildlife art by painting species such as white-tailed deer, bear, grouse, mallards, quail, and trout as game for sportsmen, and by collaborating with lithographers who made his and other’s work affordable to the American people. In addition, Tait placed his subjects in replete landscapes like those painted by members of the Hudson River School. By portraying relationships between wildlife and sportsmen, Tait distinguished himself from Audubon and his predecessors. Before Tait, human presence was not part of the imagery of American wildlife art. With Tait, sportsmen became a part of its iconography. In all, Arthur Tait produced approximately seventeen hundred paintings of which fifty-two were published by Nathaniel Currier, Currier & Ives, and L. Prang and Company. THE DIVERSIFICATION OF AMERICAN WILDLIFE ART EDWARD KEMEYS In 1870, Edward Kemeys (1843–1907), an American by birth with no formal training in art, modeled two sculptures of wolves that were subsequently cast into bronze. These works were likely Kemeys’s first castings and the first by an artist who produced a body of sculpture devoted to American wildlife. Two years later, Kemeys distinguished himself by installing the first public wildlife sculpture in the United States. Entitled Two Hudson Bay Gray Wolves Quarreling Over the Carcass of a Deer, it was cast life-size in bronze and installed in Fairmount Park in Philadelphia. With these sculptures and the body of work that followed, Edward Kemeys initiated a diversification of American wildlife art. He added sculpture as a format, depth as a dimension, and bronze as a medium. Kemeys also diversified American wildlife art by modeling predators—alone and with their prey—in addition to non-predatory species, particularly those that inhabited the American West. Kemeys worked without rival for about twenty years. His apotheosis came in 1893 with a body of work that adorned the grounds of the World’s Columbian Exposition and the Art Institute of Chicago the year after that. By this time, a second generation of sculptors such as Edward Demming, Anna Hyatt Huntington, Albert Laessle, Paul Manship, Alexander Phimister Proctor, Charles Russell, and Henry Shrady, had emerged, and they would propel wildlife art into The Twentieth Century. EARLY TWENTIETH CENTURY TO PRESENT By the time Arthur Tait died in 1905 and Currier & Ives was liquidated in 1907 (the same year that Edward Kemeys died), more American wildlife paintings and sculptures of a diverse range were being produced than ever. American wildlife art at the turn of the century was also characterized by the emergence of professionally trained artists, two of whom – Carl Rungius and Louis Agassiz Fuertes – helped fully develop the genre’s principal styles – realism and impressionism – and, by the 19-teens, bridge the art of natural history and sport into the twentieth century. In the second half of the 1920’s, Francis Lee Jaques brought diorama painting to a threshold at the American Museum of Natural History after Frank Chapman recruited him from Minnesota to New York in 1924. Duck stamps emerged in the 1930’s as a manifestation and agent of the Conservation Movement, while decorative carvings evolved out of service decoys in the 1940’s after the Great Depression. In the second half of The Twentieth Century, Stanley Meltzoff became the progenitor of so-called "dive art," while Canadian painter, Robert Bateman blended the genre with the ideology of environmentalism, and Swedish-American, Kent Ullberg advanced wildlife sculpture within the new, broad aesthetic of Post Modernism. THE ART AND INFLUENCE OF CONTEMPORARIES LOUIS AGASSIZ FUERTES Of influential and important American wildlife painters, Louis Agassiz Fuertes (1874-1927) was the first born in the United States, and the first who enjoyed success at a young age as a prodigy. While Fuertes’ predecessors were self-taught, Fuertes received training from professionals in art and science. His style endures in a significant body of work by younger artists such as Roger Tory Peterson who described Fuertes artistry in psychological terms, saying he captured the “gestalt” of the birds he painted. Fuertes modernized the art of natural history by portraying birds with a higher level of integrity than previous wildlife artists, painting characteristic attitudes, postures, behaviors, and ecology of birds in a penetrating style that revealed the inner character of birds. CARL RUNGIUS Carl Rungius (1869-1959) modernized American wildlife painting by freeing it from a style and technique of tight delineation and brushwork. Like Cézanne, who was influenced by classical balance, order, and permanence, Rungius constructed his signature paintings as carefully as if he was building them from blocks of color. Rungius fit details together to create structural solidity and stability. He sacrificed individual details to design as a whole, concentrating on basic shapes and over-all composition and design, which he painted impressionistically in broad-brush strokes. His easel paintings, sculptures, and etchings were made from the perspective of a sportsman, and sportsmen were his primary market. In addition, the paintings commissioned by the Bronx Zoo for its Gallery of Wild Animals promoted education and appreciation of wildlife among the general public. ART OF THE DIORAMA FRANCIS LEE JAQUES Francis Lee Jaques (1887–1969), a commercial artist from Minnesota, brought diorama painting to its highest threshold after Frank Chapman hired him to work at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City in 1924, and then after that, when Jaques returned to Minnesota to produce dioramas at the Bell Museum of Natural History. Jaques’ aesthetic was one of ecological didacticism; that is, he depicted wildlife against land, sky, and seascapes to reflect the interrelationships of species and their ecosystems with special attention to form and color. In contrast to Fuertes’ characterizations or Rungius’ painterly impressionism, Jaques’ wildlife images were hard-edged silhouettes, often backlit and flatly colored. By providing ecological clues such as topography and foliage, Jaques heightened viewers’ perceptions about the environment as well as wildlife ecology. Another of Jaques’ special contributions to American wildlife art image making was the depiction of wildlife within eyesight of man-made structures such as railroad tracks and farm yards—a pictorial device that reminds viewers that they are also part of the ecosystem. AMERICAN WILDLIFE ART In 1934, Roger Tory Peterson’s A Field Guide to the Birds was published by Houghton Mifflin Company. It promoted the recreational value of bird-watching and, through multiple editions and reprints in languages worldwide, became the most far-reaching book containing wildlife art in the twentieth century. The same year, Walt Disney created the cartoon character Donald Duck. THE FEDERAL DUCK STAMP Another milestone in 1934 was the enactment of the Migratory Bird Hunting Stamp Act. A special committee appointed by President Franklin D. Roosevelt, whose members included Aldo Leopold and J. N. "Ding" Darling, conceived of the federal duck stamp, as the program came to be known colloquially, to address the depletion of waterfowl populations. With it, wildlife art became a source of funds for federal game management and a powerful agent of conservation. Defined by its foremost proponent, Aldo Leopold, as "the art of making the land produce sustained annual crops of wild game for recreational use," game management relied on the notion of ecology, or "the study of the interrelationships of organisms to one another and to the environment," to resolve the nation’s wildlife resource dilemma. The first federal duck stamp print featured Richard Bishop’s 1936 federal duck stamp design of three Canada geese and was published that same year by Abercrombie & Fitch, an upscale sporting goods in New York City. THE EMERGENCE OF DECORATIVE CARVING The second quarter of the twentieth century also gave rise to a type of wildlife art known as decorative carving. It began largely through the artistry of decoy carvers such as Lemuel T. Ward (1896–1984) and Steve Ward (1894–1976) in Crisfield, Maryland, on Chesapeake Bay, and Charles Perdew (1874-1963) and Edna Perdew (1882-1974) on the Illinois River and Mississippi flyway. By the end of the Depression, the Ward Brothers had begun to take their decoys to a new level by creating innovative designs that transcended traditional service decoys. After the Ward Brothers entered and won “Best of Show” in New York in 1948 at one of the nation’s first early decoy- carving competitions, they began to embellish the shapes and painted surfaces of their carvings. Decorative carving mushroomed in the second half of the twentieth 20th Century and became part of the wildlife art genre’s modern history as evidenced by The Ward Museum of Wildfowl Art Annual World Championship Carving Competition and the collection of decoys and decorative carvings which the museum has amassed. MARINE WILDLIFE ART STANLEY MELTZOFF An altogether different development in American wildlife art emerged a decade after mid-century: the painting of fish from photographs taken underwater. Credit for this development belongs to Stanley Meltzoff (1917-2006). After Meltzoff earned an MFA from NYU and taught art and art history at City College for two years, he enlisted to serve as a World War II artist-journalist and art editor with Stars and Stripes magazine and served in Africa and Italy from 1941 to 1945. After the war, Meltzoff returned to New York to teach and illustrate magazines. From 1950 to 1955, he taught at Pratt Institute, but he gradually abandoned teaching to paint full time. For a while, Meltzoff made a living illustrating feature articles in Life and Saturday Evening Post, as well as National Geographic and other main stream magazines. In his spare time, Meltzoff pursued his other passion, diving. As noted years later in his obituary in the New York Times, ". . . even as a child in the 1920s, Mr. Meltzoff had been an avid skin diver, mainly off the New Jersey coast. By the 1940s, he was keen on spear fishing and scuba diving and, starting in 1949, he added underwater photography." As magazine assignments waned from competition from photography, necessity became the mother of invention, which led, not surprisingly given his passion for diving, to an extended career painting marine wildlife subjects. NEW AND RENEWED TRENDS IN PAINTED ROBERT BATEMAN Like any other Canadian boy with an interest in art and nature, Bob Bateman (b. 1930) idolized Canada’s Group of Seven; not only were its members household names, but their legendary travels and their robust aesthetics were celebrated in curricula taught at leading Canadian art schools across the nation. After college, Bateman set struggled with other idioms of artistic expression. ". . . I became interested in the work of Picasso and Braque and I found myself using these techniques of perspective and distortion to depict my own world . . ." An end to his search for an artistic identity came in 1963, when, after attending a retrospective exhibition of the work of Andrew Wyeth (b. 1917) at the Albright-Knox Gallery in Buffalo, New York, Bateman rediscovered the possibilities of representational painting, so much maligned by the art world in the 1940s, 1950s, and 1960s. By adapting Wyeth’s technique for his own portrayal of nature’s dramas, and by employing modern styles to shape composition and design, Robert Bateman not only found his artistic identity but advanced the aesthetic of American wildlife art yet again. Bateman also contributed to the ideology of the genre by creating hard-hitting environmental paintings in opposition to industrial-scale commercial fishing and clear-cut forestry. MODERN WILDLIFE SCULPTURE KENT ULLBERG The principal American wildlife sculptor who has worked in the postmodern idiom is Kent Ullberg (b. 1945). Ullberg also pioneered stainless steel as a medium for sculpture. Ullberg’s seminal post-modern work was Lincoln Centre Eagle, a 1981 monument commissioned for a Trammel Crow development in Dallas. Heightened inspiration came in 1984, when he heard an address by architect Philip C. Johnson while attending the annual meeting of the National Sculpture Society in New York. In May 1986, The National Wildlife Federation commissioned Ullberg to produce a sculpture fountain for a plaza formed by the addition of two buildings to the organization’s headquarters in Washington, D.C. Ullberg proposed whopping cranes as a subject to express the federation’s mission. Drawing on his love of music and the fact that cranes perform mating dances, Ullberg titled the installation Rites of Spring, after Igor Stravinksy’s radically rhythmic and dissonant ballet. Subsequent commissions have included Deinonychus Dinosaurs, a 25’ monument on Logan Square in Philadelphia; Sailfish in Three Stages of Ascending, the centerpiece of The Broward Convention Center Marine Fountain, a 120’ by 150’ installation of bronze, granite, and water, in Ft. Lauderdale, FL; and his First National Bank Spirit of Nebraska’s Wilderness monument in Omaha. SPONSORS OF AMERICAN WILDLIFE ART, THE BOOK

REVIEWS AND BLOGS Arts Around Town: ‘Best of the best’ in American Wildlife Art exhibit at Allentown Art Museum ~ Review by Susan Kalan LENDERS Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University, Philadelphia, PA Exhibition photos that follow are from the premiere of AMERICAN WILDLIFE ART

|